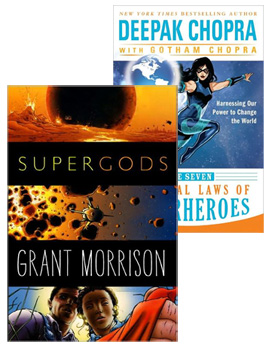

Five years ago, at the San Diego Comic-Con, Grant Morrison and Deepak Chopra packed an exhibit hall talking about superhero comics as blueprints for the next stage in human consciousness. So when I discovered they were each publishing a book on the subject this summer, I was curious to see how they’d extend that initial conversation about archetypes and evolutionary allegories as filtered through Pop Art. Neither book is exactly what I was hoping for, but one of them did turn out to be genuinely inspired… and a bit inspiring as well.

Let’s take out the easy target first: The Seven Spiritual Laws of Superheroes displays a limited understanding of superhero comics at best. That’s not surprising, given that said understanding seems to come largely from Chopra telling his son, Gotham, how he thinks spiritually enlightened beings should behave, and Gotham telling him there’s a character who’s sort of like that. Conseqeuently, he says things like “For every challenge, the superhero’s solution is to go inward,” which makes you wonder what he thinks all the fight scenes are there for.

In Chopra’s formulation, superheroes “have no personal stake in this war [against evil],” and strive “to reach unity consciousness” (roughly equivalent to Buddhist enlightenment) “not intellectually, but experientially.” I’ll tell you: The first two comic book characters who come immediately to mind based on those criteria are Dr. Manhattan and Ozymandias from Watchmen—among the best examples of everything that can go wrong pursuing the superheroic dream. That’s also the case with one of the touchstones Chopra himself offers, pitching the Dark Phoenix saga as a model for how “real superheroes… don’t just tap into the field of infinite power and consciousness, they become it.” He ignores the crucial point that Jean Grey is driven mad by that transformation and kills herself rather than allow it to continue.

(My favorite bit, though, is when Chopra announces that “superheroes don’t waste time or energy in self-righteous morality or judgment of the moral actions of others,” which makes me want to send him a copy of Steve Ditko’s Mr. A and blow his mind.)

The stopped clock principle ensures some comic book stories will conform to Chopra’s templates, but the fundamental problem is that he comes to the field not just as an outside observer, but one who’s already decided what he’s going to find. In contrast, one of the greatest strengths of Grant Morrison’s Supergods is the intensity of his fandom—he always starts from the stories themselves, digging into the scripts and the visual compositions, teasing out themes and subtexts as he goes along. He treats comics with the same meticulous scrutiny Greil Marcus brought to punk rock in Lipstick Traces, equally at home describing the formal elements of the Action Comics #1 cover or the rich cadences of a Roy Thomas script.

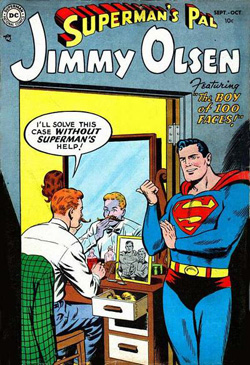

Sometimes the path gets a little weird, like the proposal that Jimmy Olsen is the precursor of David Bowie and Lady Gaga’s parades of fluid identities. Sometimes it gets a lot weird, like the invocation of ceremonial magic’s Holy Guardian Angel to describe Captain Marvel as Billy Batson’s “exalted future self.” And sometimes, like the description of Morrison’s own encounter with extradimensional life forms in Kathmandu, the path temporarily ceases to exist.

Sometimes the path gets a little weird, like the proposal that Jimmy Olsen is the precursor of David Bowie and Lady Gaga’s parades of fluid identities. Sometimes it gets a lot weird, like the invocation of ceremonial magic’s Holy Guardian Angel to describe Captain Marvel as Billy Batson’s “exalted future self.” And sometimes, like the description of Morrison’s own encounter with extradimensional life forms in Kathmandu, the path temporarily ceases to exist.

The autobiographical elements, though, are fundamental to Morrison’s understanding of comics, so much so that when his historical recap reaches 1960, he announces, “This is where I joined the continuity.” If comics can function as a catalyst for personal transformation, we need to understand their role in Morrison’s own self-reinventions, not just as a reader of comics but as a writer. The sections on his symbiotic bond with series like Doom Patrol, Flex Mentallo, and The Invisibles are among the book’s most compelling, and they shed light on his interpretations of all the other comics that came before.

I do wish Morrison had spent some more time on delving into his own approach to Batman, laying out the argument he’s made in several interviews over the years about how Bruce Wayne’s relentless training produced radical self-actualization. That could have tied in to an more explicit discussion of the themes promised in the book’s subtitle: “what masked vigilantes, miraculous mutants, and a sun god from Smallville can teach us about being human.” I suppose to some extent I was expecting something like Morrison’s famous essay on “Pop Magic,” which not only talks about superheroes as avatars representing states of consciousness but also provides instructions on how to summon them into your own life.

The danger with that approach, however, is that it could easily have fallen into the same trap The Seven Spiritual Laws of Superheroes did—falling so in love with its shiny formula that the wild, chaotic evidence gets lost. And, as Morrison fully understands, the chaos is a huge part of what makes comics (and the other cultural phenomena spinning off from them) so much fun. One of Morrison’s most famous Justice League stories, “World War III,” ended with everyone on Earth becoming a superhero. It’s an ideal metaphor for how each of us can draw a different inspiration from the comic-book universe and, with perseverance and maybe a bit of luck, incorporate that creative vision into our own lives.

Ron Hogan is the founding curator of Beatrice.com, one of the first websites to focus on books and authors. Lately, he’s been reviewing science fiction and fantasy for Shelf Awareness.